DOMESTIC CAPITAL:

An Experimental Studio

Studio Tutor

A/P Dr. Lilian Chee and Tan Yi-Ern Samuel,

Assisted by Phua Yi Xuan Anthea, Wong Zi Hao

Level

NUS, M.Arch (1), AR5802

Academic Year

2021/2022, Semester 2

Type

Design Studio

Students

Rebecca Chong Shu Wen, Lim Kun Yi James, Yap Pei Li, Beverly, Choi Seung Hyeok, Pennie Kwan Jia Wen, Wan Nabilah binte Wan Imran Woojdy, Ye Thu, Tan Wei Jie, Eugene

Reviewers

Dr Constance Lau, University of Westminster Prof CJ Lim, Bartlett School of Architecture, UCL

Siddharta Perez, Senior Curator, NUS Museum

Adj Asst Prof Peter Sim, FARM

Tham Wai Hon, Tacit Design

Marianna Janowitz, Edit Collective

Film Place Collective (Sander Hölsgens, Rebecca Loewen, Thi Phuong-Trâm Nguyen)

Making Do Research Team (Prof Jane M Jacobs, Yale-NUS, Prof Audrey Yue, Communications and New Media, NUS Dr Natalie Pang, Communications and New Media, NUS)

Ribbon Image: Tan Wei Jie Eugene

SELECTED WORKS

-

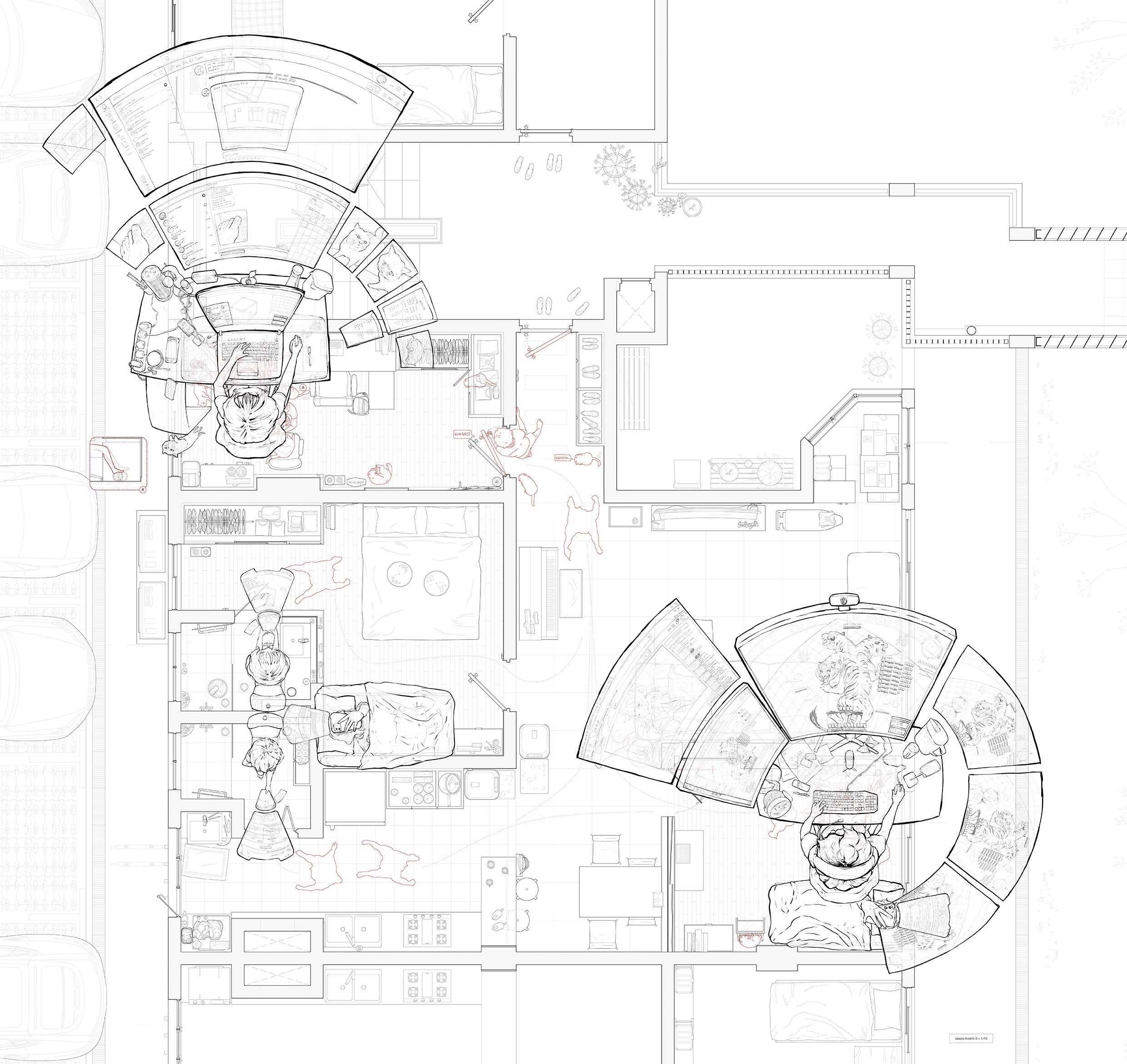

by Rebecca Chong Shu Wen

A computer screen is flat, and yet paradoxically spatial. The digital spaces hold our attention for a majority of our waking hours, and keeping us sufficiently satisfied without having to leave the 500mm radius of our chair and desk. Workspaces, sources of social stimulation, entertainment, are all instant and accessible, nothing but a reflexive wrist flick of a mouse or a keyboard entry away. A computer UI tells us everything and anything instantly, with constant stimuli in the form of notifications signalling the gaps in our information.

Reality pales in comparison as it appears unchanging, or even daunting; there isn’t an overworld notification system that tells us when the sun is starting to set, or what’s the next task in the main quest of life; and the extent of reality which we are willing to navigate decreases as more of our lives move online.

With more of our lives being converted to a digital existence, such that we become digital workers, this project seeks to offer a design interpretation that productively disrupts virtual time and space through natural, nature-bound, or spontaneous occurrences. What kind of physical conditions would then prompt us to engage more with our physical spaces, productively drawing us out of our self-contained digital bubbles where work, entertainment and everything but reproductive breaks and toilet breaks take place?

The project seeks to create a device that mediates the interior and exterior by dilating the space between them, in the process nurturing a sensitivity in occupants towards occurrences beyond the supposed boundary of the flat. The vestibules created by puffing up the space create a degree of translucency between what’s considered outside and inside. Where previously a 200m thick wall marked the end of the exterior and the beginning of the interior, this boundary is puffed up into a vestibule. Instead of unthinkingly reaching out in the general direction of the window to draw a curtain shut while not taking one’s eyes off the screen, the occupant has to bodily manoeuvre and turn to the window, in the process being rewarded with a view of the sunset and also a chance to pamper the cat.

Eventually these occurrences start to shape a way life that embraces interruption and rest time. In being more attuned to these “real-life notifications”, the monotony of the digital space is regularly and productively punctuated by a gamut of interruptions, from the warbling of a bird to that one cat that is insistent on getting the attention it rightfully deserves.

-

by Tan Wei Jie Eugene

Maps are often the starting point in the design of architecture. Yet these maps often value measurability, precision, and objectivity over other qualities. In omitting information about materiality, history, and culture, these maps often reduce a site to a shape on paper. In Singapore, where land is scarce, this means of representation is particularly useful as it ascribes the value of land to its size, allowing authorities to make economic decisions about the use of land.

The documentation phase critiques this neoliberal paradigm in valuing land. In Kampong Lorong Buangkok, the huge site has been earmarked for redevelopment into a three- lane expressway due to economic methods of valuation. In exploring the site as opposed to studying it from a map, I argue that land cannot be valued for its size, but rather should be valued for the community, the way of life, and the narratives that had defined the village. Using the same methodology of mapping, the documentation phase explores a series of alternative maps, that argue that the value of land is more than its size, but rather the ecology, the narratives, and the events that have happened on the site.

However, maps that are created in the cartographic frame are always limited by the limitations of the cartographic profession. In the design phase, mapping is explored through the architectural frame. An archatographic map is proposed, which subverts conventions like the rectangular frame, the material of paper, and conventions like the north arrow or the grid.

Envisioned as a map in 2038 when the Kampong has been cleared for redevelopment, the archatographic map allows one to navigate around the site by carrying it around. By orientating and navigating using landmarks and pacing, the slow process of navigating reveals stories and artifacts that once existed on the site. In the absence of the kampong, the map seeks to embody the experience of living on the site, allowing visitors to experience the kampong from the perspective of a resident.

Lastly, in the absence of the original kampong, as different visitors move around the site using the archatographic map, their engagement with the map creates different spaces that rely on their interpretation of the site and map. This spatial response contradicts the fixity of architecture, revealing the biases of architectural maps that we often overlook.

-

by Lim Kun Yi James

With the compression of maintenance services from specialised industries with large dedicated infrastructures, to compact ubiquitous machines within the home and its proximities, laundry has been naturalised and conferred a lesser value in tandem with its increasing access and convenience. Laundry at large assumes an invisible labour, only foregrounded when it accumulates, or when inclement weather forces it to decommission parts of the house

to accommodate its presence. With the chronic undervaluing of laundry, comes along the lack of affordance to its changing spatial requirements as it migrates within and beyond the house. Space for this invisible labour becomes a concession, relegated to the unseen and often poorly planned immutable service spaces.

Laundry, particularly its drying process, occupies a cyclical spatial and temporal presence within the house, it serves as an indicator of interior microclimates and ritual, amplifying its’s role as a social condenser. The fragrance of detergent and UV light, the fluttering of sheer fabric in the breeze, the static sound of

rain, and calls of impending rain echoing through the height of the hdb block, instantiate the observed aesthetic experiences of laundry and its time-scales on site of the high-rise flat. Consequently the migration of laundry forms the key fascination towards the varying conditions of laundry and its spatial, social and atmosoheric productions within and beyond the flat.

The project spurs the rethinking of space and presence of laundry in the high-rise block by imagining the flat as a laundry machine. Its interior walls become permeable letting laundry to dry between them, curling and uncurling in response to humidity, wind and heat from both exterior climate and

laundry loads. The exploration assumes the format of a sequence of laundry choreography, spanning three months during the northeast monsoon as the flat experiences the wettest December month and eventually transitions back into the intermonsoon season in early March.

The design requires the development of a material that responds to the atmospheric changes brought about by and for the facilitation of laundry, and in doing so, spatially relocating laundry out of the recesses of the home, within which they are typically programmatically confined into interactive spaces in the home. This requires the flat to assume an entirely porous condition and the material offers a way to tune the degree of porosity, both in the it’s natural response to the environment and changes imposed by the occupant

-

by Pennie Kwan Jia Wen

During circuit breaker, many Singaporeans came together and brought about the house plant boom, bringing dozens of plants into their home as a form of self-care. In introducing these fragile and dependent beings to the home, routines and mini environments began to be formed around the plant at home and the spaces in which they share with people. The standard home environment has been altered by their inhabitants, likely creating uncomfortable spaces for humans but not the plants. Windows are filtered by leaves, the air-conditioner is rendered useless in the living room, it gets extra humid when it rains... Yet, house plants are still being kept. The domestic labour of caring for the home began to evolve to include these “useless” houseplants, developing new instinctive and bodily knowledge of care - differentiating weight of dry pots, observation of leaves and roots and acknowledging weather - towards plants, specifically in the home, where people are treating houseplants as equal residents.

Increasingly, HDBs are being built under a build-to-order scheme in which many Singaporeans fill in applications to projects before tender. Can houseplant parents choose instead to have options that allow them to change their conventional spaces to ones that are devoted to the living of houseplants?

The start of this project focused on the documentation of a plant home and the lifestyle surrounding the care for house plants. The second half of the semester, aims to look at house plants, not as objects of exploitation but as equals by re- centering the plant and the occupant and giving them their own dedicated space within a the HDB. By giving plants their own space, we see what can be given up from spaces originally meant to be for human occupation. In A Humid Home, the posible scalar impacts of what happens to a whole block of flats when one focuses on something as small as a houseplant becomes apparent.

-

by Wan Nabilah binte Wan Imran Woojdy

The loss of the Ramadan bazaar in 2020 was deeply felt by the Muslim community. More than just a marketplace, the seasonal traditional event acts as an anchor and barometer for Malay-Muslims to renew and reaffirm their sense of self and place in an act of negotiating identity as a minority group in Singapore (Ismail & Shaw, 2014). Home bakers struggled to compensate, working furiously from the restricted confines of their flats, transforming the house from a site of consumption to a site of production. The loss of festive space led to the exuberance of Ramadan festivities to be downplayed, making it difficult to manifest and preserve the community’s ethno-religious identity, as these were entangled with the production of festive foods.

The Bakers’ Brigade is a speculative narrative project which imagines the work of home-based baking in a floating city that is unmoored from the land, predicated upon the present-day deprivation of festive space, for the use of cultural expression. The fantastical elements in the project shape a world and a way of life where festive celebration is reframed as productive work that reaffirms and preserves the community’s rich cultural heritage. Heat, smoke, scents – elements that are typically siphoned away in architecture, are instead harnessed to rise the Baker’s Quarters into the sky in a celebratory migration, free from the uncertainty of a physical site, to bring good food and good cheer to all.

-

by Ye Thu

In Holding Space, I explore alternative ways through which architecture is represented, centring and giving weight to my own experience as a Burmese immigrant living in a HDB flat. In the film, I document various forms of reproductive labour done around flats of other Burmese immigrants that are contrasted with scenes of me performing and recreating these scenes within the 4x3m bedroom of my flat.

Depicted in the film, I attach mirrors onto my windows and primarily capture my performance through the mirrors’ reflections with the camera never leaving beyond the windows. I argue that the home-space of the HDB flat as lived and experienced by a minority immigrant exists as much through this imagined gaze as it does through actual reality. This gaze is a resultant of asymmetrical power dynamics and both imagined and actual surveillance from adjacent flats and external corridors that more often than not alters one’s own behavior in the house through a heightened awareness of the self. The scenes in the film are to be read as my own perception of how others living across, above and below me would see me and the space if I were to be praying, eating, hanging laundry, etc; they are not objective, calculated, nor precise recreations of potential views inward; they are subjective and personal.

The project critiques the way in which architects visualise and instrumentalise their modes of seeing. The way in which the project is filmed departs from the conventions of how architecture is usually viewed and imbued with meaning - through plans, elevations, and sections. Even personified architectural perspective drawings that are supposed verifications of physical truth and experience exist in isolation from one’s own spatial reading and imagination; again privileging objectivity and architectural tectonics above subjective experience and the imagination . The making of the film and the capturing of these imagined views challenges both the integrity and usefulness of these ways of seeing.